Chausson: Piece for cello & piano (1897)

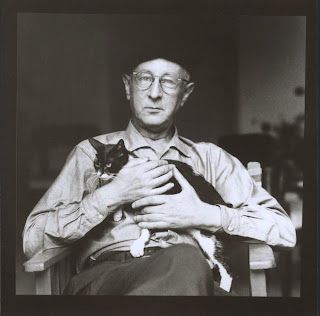

Standing: Mme Chausson, Ernest Chausson, and Raymond Bonheur.

Seated on the ground: Claude Debussy

In 1893, Claude Debussy wrote to Ernest Chausson,

Music really ought to have been an

hermetical science, enshrined in texts so hard and laborious to decipher as to

discourage the herd of people who treat it as casually as they do a

handkerchief! I'd go further and, instead of spreading music among the

populace, I propose the foundation of a 'Society of Musical Esotericism'.

His words project a sense of the place and times, ca.

1871-1914, that we call 'Belle Époque Paris', the focus in Europe for the

symbolist movement in poetry, and impressionism in painting and music.

Putting to one side the artist's disdain for an

uncomprehending audience (imagined or real), it's difficult now to understand

just why the music of this era, which audiences today rarely consider

'difficult', was labeled 'decadent' and worse. A major justification was the

often cited violations of the holy trinity of Western music – melody, harmony and rhythm. One critic wrote

about a new work that it '[abolishes] rhythm, melody and tonality from music

and thus [leaves] nothing but atmosphere.' But critics' focus on these

compositional elements was not completely off the mark. If that critic, instead

of writing 'abolishes' had written 'reimagines

rhythm, melody and tonality' he would have been on to something. A case in

point is the 1897 Piece for cello and

piano by Ernest Chausson.

Ernest Chausson (1855–1899)

Piéce, Op. 39

Javier Albarés Alberca, cello, Javier Estebarán Crespo, piano

El Jardin de Belagua, 2010

The piece opens under the time signature 54

(five quarter-notes in every bar). This is uncommon in Western music of the

17th-19th centuries where the numerator (number of beats in a bar) is nearly

always divisible by 2 or 3 (24, 34,

68, 44, etc.), but it's not unheard

of. The second movement of Tchaikovsky's 6th Symphony is written in 54.

The way Tchaikovsky handles this is by splitting the 5 into 2+3 beats in every

bar, so the effect is a repeating accent pattern 1-2/

3-4-5 / 1-2/

3-4-5 / etc. The overall effect is a

slightly off-kilter waltz. In his piece Chausson splits 54

the same way, but there is no suggestion of a waltz. For one thing, Chausson's

tempo is much slower, and this leaves room for him to 'play' within and across

the bar lines. Often the phrasing of the melodic line subtly splits the bar

differently, so one part in the piano might express the 2+3 division while the

cello phrases its melodic line to split the bar evenly 2-1/2

+ 2-1/2. Things get even more complex about half way

through the piece when the time signature switches to 74.

The overall effect of contrasting meters creates an asymmetry that suggests a

poem in free verse.

By now our Belle Époque critic is tearing his hair out,

thinking up new pejoratives while trying to find the beat. Fortunately,

audiences today have come to learn that to enjoy the beauty in a work such as

the Chausson Piece, we only need to

relax and just listen.

–– Program Notes for Charlottesville Chamber Music Festival by Stephen Soderberg (2016)

Comments

Post a Comment