Martinů

|

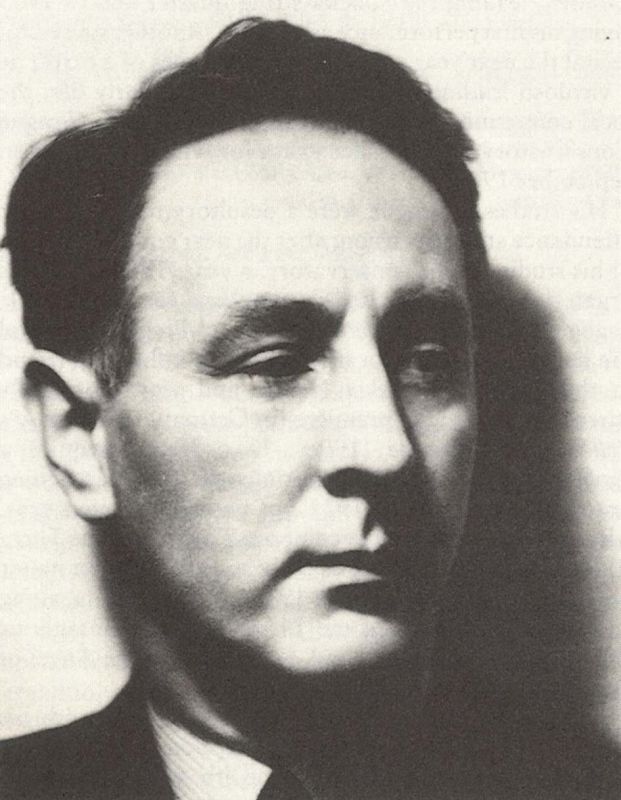

| Bohuslav Martinů (1890–1959) |

"A system of uncertainty has entered our daily life. The pressures of mechanization and uniformity to which it is subject call for protest and the artist has only one means of expressing this, by music."

By 1942 Stravinsky had already turned Europe upside down with The Rite of Spring, and Schoenberg had turned it inside out with his “method of composition with twelve tones related only to one another.” 1942 found Schoenberg living in Hollywood, California – his regular tennis partner was George Gershwin. Stravinsky had moved to the United States as well; he lived less than a mile from Schoenberg, but they never spoke to one another.

By now the world of music had begun to test its outermost boundaries: Aaron Copland, a former student of Nadia Boulanger, composed the score for the ballet Rodeo in 1942, the same year a former student of Schoenberg, John Cage, composed Imaginary Landscapes 2 & 3 for percussion ensemble. But the American scene was no longer dominated by Europe. Ironically, both Copland and Cage, polar opposites in so many ways, could justifiably claim to be the heirs of the first certifiably all-American composer, Charles Ives. Copland especially demonstrated that music both radical and conservative, complex and simple, elitist and populist, could spill from the same pen. After World War II, Europe and the United States together represented the most diverse – some would say fragmented – musical culture ever known.

Blacklisted by the Nazis, Martinů left Paris and fled to America, moving to Jamaica, New York in 1941. The Piano Quartet was one of the first works he completed in his new home. Despite his admiration for the French tradition (he studied with Albert Roussel and lived in Paris for more than fifteen years), and despite the proliferation of atonal experiments going on all around him, he remained a Czech nationalist with a deep feeling for his native musical roots. While his technique was deeply affected by Ravel and the Impressionists’ innovations, his music still retained some unmistakable marks of his Czech predecessors and contemporaries.

Blacklisted by the Nazis, Martinů left Paris and fled to America, moving to Jamaica, New York in 1941. The Piano Quartet was one of the first works he completed in his new home. Despite his admiration for the French tradition (he studied with Albert Roussel and lived in Paris for more than fifteen years), and despite the proliferation of atonal experiments going on all around him, he remained a Czech nationalist with a deep feeling for his native musical roots. While his technique was deeply affected by Ravel and the Impressionists’ innovations, his music still retained some unmistakable marks of his Czech predecessors and contemporaries.

Bohuslav Martinů – First Piano Quartet

I. Poco Allegro

The Quartet begins with a terse three-note motive passed between the violin and the viola. This urgent, declamatory motive which appears throughout the first movement in many guises, soon gives way to a more expansive and “sinuous” theme shared between the strings, an idea that will form the basis for the last movement. After this theme is established, the cello introduces a new idea below that has traces of Moravian folksong – an idea that is developed into a broader version presented later by the violin.

II. Adagio

Throughout the first movement the piano is of equal importance with the strings. In stark contrast, the adagio second movement begins with an extended passionate trio for the strings alone. This is followed by a mysterious middle section with the piano playing rapid roulade-like surfaces over muted strings. The piano again falls silent, and the movement ends the way it began, with unaccompanied strings. Simple and, in Martinů’s hands, highly effective.

III. Allegretto poco moderato

This entire quartet is full of common twentieth-century harmonic techniques – parallel fourths, chords created by stacking thirds and fourths and so on – nothing that, taken alone, is difficult for our ears today. But perhaps the most striking thing about this piece – what generates its energy and holds it together formally – is its rhythmic structure at all levels.

It is common in many European folk traditions for triple rhythms to alternate with duple to create interesting syncopations. In this work Martinů, following the lead of Stravinsky, Bartók and others, took this subtle folk practice many steps further, elevating it to a construction principle. The “sinuous [intricate, complex, winding] theme” noted above (the phrase is musicologist Ian Bent’s) now forms the basis for the much more complex rhythmic formations that generate the final movement of the quartet.

The solo piano opens the last movement softly. The overall effect is a gentle rocking feeling – not the sleep-inducing, regular rocking of a cradle, but the mesmerizing irregular rocking of a rowboat tied to a pier. What is happening here (remember the duple-triple alternation idea) is that the right hand is playing with unexpected combinations of 2- and 3-beats:

This amazing work as a whole only makes sense during the final movement. This is due in great part to the tendency in this music, as in so many twentieth-century works, toward “prefiguration.” The romantic age developed the idea of “recall” (think of the introduction to the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony). By the twentieth century this idea was turned around such that seemingly irrelevant, out-of-place material introduced earlier in a work only becomes relevant near the end. This is one of the reasons that twentieth-century works still demand several hearings, even today, before they can be appreciated and assimilated. It is not so much the “dissonance” that confounds many listeners (motion picture soundtracks have made “dissonance” almost unnoticeable to us anymore), but rather the demand on the listener to connect musical events often separated by wide temporal distances.

The solo piano opens the last movement softly. The overall effect is a gentle rocking feeling – not the sleep-inducing, regular rocking of a cradle, but the mesmerizing irregular rocking of a rowboat tied to a pier. What is happening here (remember the duple-triple alternation idea) is that the right hand is playing with unexpected combinations of 2- and 3-beats:

2-2-2-3-2-3-2-3-2-2- ...

while, at the same time, the left hand is playing a more regular pattern of 2’s broken by an occasional 3:

3-2-2-2-2-2-2-2-3-2- ...

Continuing with the rocking boat analogy, the entire movement can be heard as what happens to the boat as the water becomes agitated, calm, placid, churning.This amazing work as a whole only makes sense during the final movement. This is due in great part to the tendency in this music, as in so many twentieth-century works, toward “prefiguration.” The romantic age developed the idea of “recall” (think of the introduction to the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony). By the twentieth century this idea was turned around such that seemingly irrelevant, out-of-place material introduced earlier in a work only becomes relevant near the end. This is one of the reasons that twentieth-century works still demand several hearings, even today, before they can be appreciated and assimilated. It is not so much the “dissonance” that confounds many listeners (motion picture soundtracks have made “dissonance” almost unnoticeable to us anymore), but rather the demand on the listener to connect musical events often separated by wide temporal distances.

With this in mind, for the listener who remains perplexed after listening through this work the first time, it might be helpful to listen to the last movement three, four or five times – then return and listen to the entire work again from the beginning. This wonderful music is worth the effort.

Martinů First Piano Quartet

Performed by the Josef Suk Piano Quartet*

Performed by the Josef Suk Piano Quartet*

_____________________

* Vaclav Macha pianoforte, Radim Kresta violino, Eva Krestova viola, Vaclav Petr violoncello

(Czech Republic, Slovak Republic. Winners of the 14th international Trio di Trieste Competition. "Victor de Sabata" Hall of the Verdi Theater in Trieste. 7 September 2013)

Comments

Post a Comment