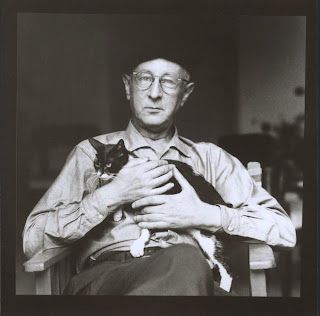

Takemitsu

|

| Mountains in central Hokkaido |

Composer Toru Takemitsu begins his essay “Nature and Music” [i]with these words:

This summer [1962], walking through the fields of Hokkaido, I could not help thinking that my own thoughts have come to resemble the sidewalks of a city: rigid and calculated.

This is a fascinating sentence. Like a “good theme” in music,[ii] it holds a potential composition like a seed holds a potential plant.

It’s tempting to take the first half of the sentence,

This summer [1962], walking through the fields of Hokkaido,

I could not help thinking ...,

as colorful but superfluous – a kind of grace note attached to the real theme expressed in the rather gray analogy,

... my own thoughts have come to resemble the sidewalks of a city:

rigid and calculated.

But the seemingly superfluous “information” in the antecedent – season and location – actually offers a perspective helpful in understanding Takemitsu’s genius (in the ancient sense of “generative power”) and perhaps the Japanese cultural genius as well.

Take what has become the most famous of all Japanese poetic forms, the haiku. If we ignore the supposed technical requirement of 17 “on” arranged as three lines of 5, 7, and 5 “syllables,”[iii]we might arrange our superfluous grace note into a free-form haiku:

Walking through the fields of Hokkaido

This summer

I could not help thinking

Hallmarks of haiku are here without having to count to 17: a seasonal reference, “summer,” a reference to nature, “the fields of Hokkaido”, and “this summer” serves to “cut” the apposition of “walking” and “thinking.” Maybe that’s far-fetched, but not nearly so as any attempt to do the same to the sentence’s consequent. For example,

Rigid and calculated

My own thoughts –

Sidewalks of a city

No matter how you put it together, it’s prosaic. Nevertheless, both antecedent and consequent occupy the same world, which we now see in Takemitsu’s approach to the problematic human element – “the tawdry and seamy side of human existence” – in Nature and Music.

... Standing there in a field with an uninterrupted view of forty kilometers, I thought that the city, because of its very nature, would someday be outmoded and abandoned as a passing phenomenon. The unnatural quality of city life results from an abnormal swelling of the nerve endings.

. . . .

A lifestyle out of balance with nature is frightening. As long as we live, we aspire to harmonize with nature. It is this harmony in which the arts originate and to which they will eventually return.

... I believe what we call ‘expression’ in art is really discovery, by one’s own mode, of something new in this world. There is something about this word ‘expression,’ however, that alienates me: no matter how dedicated to truth we may be, in the end when we see that what we have produced is artificial, it is false. I have never doubted that the love of art is the love of unreality.

Although I think constantly about the relationship of music to nature, for me music does not exist to describe natural scenery[!] While it is true that I am sometimes impressed by natural scenery devoid of human life, and that may motivate my own composing, at the same time I cannot forget the tawdry and seamy side of human existence. I cannot conceive of nature and human beings as opposing elements, but prefer to emphasize living harmoniously, which I call naturalness. ... In my own creation naturalness is nothing but relating to reality. It is from the boiling pot of reality that art is born.[iv]

. . . .

I wish to free sounds from the trite rules of music, rules that are in turn stifled by formulas and calculations. I want to give sounds the freedom to breathe. Rather than on the ideology of self-expression, music should be based on a profound relationship to nature – sometimes gentle, sometimes harsh. When sounds are possessed by ideas instead of having their own identity, music suffers.

. . . .

Takemitsu, Rain Tree Sketch for three percussionists.

(Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center)

Takemitsu, Rain Tree Sketch II, for piano.

In memoriam Olivier Messiaen.

(Peter Serkin)

[i]“Nature and Music” is the first essay in Confronting Silence, selected writings. Toru Takemitsu. Tr. & ed. Yoshiko Kakudo and Glenn Glasow (1995)

[ii]“’A good theme is a gift of God,’ [Brahms] said; and he concluded with a word of Goethe: ‘Deserve it in order to possess it.’” – Arnold Schoenberg, “Heart and Brain in Music” (1946)

[iii]The notion that a haiku must have 17 “syllables” corrupts the form in Japanese which often (but certainly not always) calls for 17 “on” which means “sound.” A fairly good non-popularized sense of haiku can be found here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haiku. More about the distinction between “on” and “syllable” can be found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_(Japanese_prosody). Readers who want to do a deep dive (in English) into the form, its relationship to Zen, and surprising connections to western literature can hardly do better than the works of R. H. Blyth (bio & bib at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reginald_Horace_Blyth). Blyth was an accomplished violinist and cellist who spent WWII as a “detainee” in Korea and Japan, often playing western chamber music with several of his Japanese guards.

[iv]Goethe to Eckermann: “[R]eality must give both impulse and material. ... Reality must give the motive, the points to be expressed – the kernel; but to work out of it a beautiful animated whole belongs to the poet.”

Comments

Post a Comment