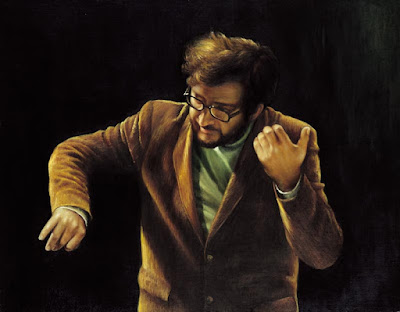

The Basics: Berio's Duetti

Image courtesy of Naxos Records Luciano Berio (1925–2003) Duetti for two violins It can happen that a violinist friend tells a composer one night that, other than those of Bartók, there are not enough violin duets today. And it can happen that the composer immediately sets himself to writing duets that night until dawn… and then more duets in moments of leisure, in different cities and hotels, between rehearsals, travelling, thinking of somebody, when looking for a present... This is what happened to me and I am grateful to that nocturnal violinist whose name [musicologist Leonardo Pinzauti (1926–2015)] is given to one of these Duetti . [1] This is how Luciano Berio described the genesis of the 34 Duetti for two violins. With the exception of the first duet – a nod to those Bartók violin duos – each of the pieces is associated with one of his friends, inspired by "personal reasons and situations" and connected by "the fragile thread of daily occas