Jazz in the Soviet Union & Beyond

|

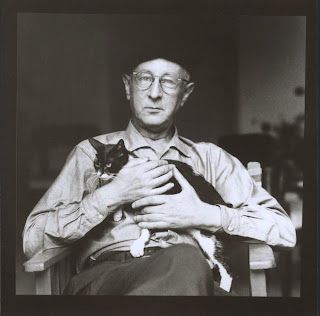

| Nikolai Kapustin (1937–) |

Nikolai Kapustin: Piano Quintet, Op. 89

Nikolai Kapustin once wrote, “In the early ’50s jazz was completely prohibited, and there were articles in our magazines that said it was typical capitalistic culture, so we have to throw it away and forget about it.” With occasional respites, this situation lasted well beyond the Stalin years into the Krushchev and even Brezhnev regimes.

But forbidden fruit had always managed to survive the censors in two ways. One was “samizdat” (self- published) and the other, “tamizdat” (published abroad and smuggled in). Jazz and popular Western music were particularly difficult to get because there were few machines to play vinyl recordings or tapes. Yet American and Western European records were still snuck in and shared among the few who had record players.

Samizdat sound recordings were produced on home made record lathes. Some enterprising Russian jazz- lover had discovered that x-ray film is soft enough to be recorded on, but strong enough to hold the groove, and there was a plentiful supply of x-rays discarded by hospitals. These recordings (which “sounded like sand”) were known, with the characteristic dark humor of the time, as “ryobra” (ribs). This was the atmosphere in which Nikolai Kapustin became a composer.

In 1953 Josef Stalin died – and Kapustin at age 16 heard jazz for the first time over the radio at a friend’s house. He had already begun to study as a pianist. Political attitudes about jazz temporarily became more permissive, but his teachers at the conservatory where he studied the classics were still a problem. He wrote, “Maybe the government looked at jazz with some suspicion, but it seems to me that an attitude to jazz of some professors of conservatories is much worse.” By day he was a piano student playing classical music at the conservatory. By night he played jazz with his friends.

But while he was soaking up jazz techniques and attaining notoriety as a jazz pianist, both in State-approved big bands and in clubs, he was not really happy facing a career as a jazz pianist. He wanted to compose music that synthesized classical forms and jazz textures – music that used the language of jazz improvisation but does not improvise. As one writer put it, “a jazz vernacular presented in a contrapuntally dense framework of thematic organization, development, and restatement” – something more integrated even than Gunther Schuller’s Third Stream.

The irony resulting from following his natural inclination was that he was able to sneak under the censors in broad daylight. He may have raised some eyebrows, but his jazz-infused forms were within the bounds of what was taught at the conservatory. His music wasn’t the sort of freewheeling jazz that challenged authority – it was not judged as “blatnaya pesnya” (roughly, “criminal” or “prison” music). As of today, Kapustin has published over 600 works. Most of them are built on traditional “classical” forms, but all of them swing.

An excellent example of Kapustin’s fusion of form and style is found in his 1998 Piano Quintet. The first movement, Allegro, is full of sweeping gestures and marked by cascading jazz roulades in the piano. The second movement, Presto, is a wickedly angular little scherzo; don’t blink – it’s over before you know it. The beautiful slow movement, Lento, concentrates on the strings in the closest thing in this work to a romantic style. Finally, The Allegro non troppo is a tour de force of fusion that one critic has called a “jazz-rock classic.” Perhaps that’s an overstatement, but it is guaranteed that audience and performers will be breathless at the end.

(Program note by Stephen Soderberg for the 2017 Charlottesville Chamber Music Festival)

Nikolai Kapustin once wrote, “In the early ’50s jazz was completely prohibited, and there were articles in our magazines that said it was typical capitalistic culture, so we have to throw it away and forget about it.” With occasional respites, this situation lasted well beyond the Stalin years into the Krushchev and even Brezhnev regimes.

But forbidden fruit had always managed to survive the censors in two ways. One was “samizdat” (self- published) and the other, “tamizdat” (published abroad and smuggled in). Jazz and popular Western music were particularly difficult to get because there were few machines to play vinyl recordings or tapes. Yet American and Western European records were still snuck in and shared among the few who had record players.

Samizdat sound recordings were produced on home made record lathes. Some enterprising Russian jazz- lover had discovered that x-ray film is soft enough to be recorded on, but strong enough to hold the groove, and there was a plentiful supply of x-rays discarded by hospitals. These recordings (which “sounded like sand”) were known, with the characteristic dark humor of the time, as “ryobra” (ribs). This was the atmosphere in which Nikolai Kapustin became a composer.

In 1953 Josef Stalin died – and Kapustin at age 16 heard jazz for the first time over the radio at a friend’s house. He had already begun to study as a pianist. Political attitudes about jazz temporarily became more permissive, but his teachers at the conservatory where he studied the classics were still a problem. He wrote, “Maybe the government looked at jazz with some suspicion, but it seems to me that an attitude to jazz of some professors of conservatories is much worse.” By day he was a piano student playing classical music at the conservatory. By night he played jazz with his friends.

But while he was soaking up jazz techniques and attaining notoriety as a jazz pianist, both in State-approved big bands and in clubs, he was not really happy facing a career as a jazz pianist. He wanted to compose music that synthesized classical forms and jazz textures – music that used the language of jazz improvisation but does not improvise. As one writer put it, “a jazz vernacular presented in a contrapuntally dense framework of thematic organization, development, and restatement” – something more integrated even than Gunther Schuller’s Third Stream.

The irony resulting from following his natural inclination was that he was able to sneak under the censors in broad daylight. He may have raised some eyebrows, but his jazz-infused forms were within the bounds of what was taught at the conservatory. His music wasn’t the sort of freewheeling jazz that challenged authority – it was not judged as “blatnaya pesnya” (roughly, “criminal” or “prison” music). As of today, Kapustin has published over 600 works. Most of them are built on traditional “classical” forms, but all of them swing.

An excellent example of Kapustin’s fusion of form and style is found in his 1998 Piano Quintet. The first movement, Allegro, is full of sweeping gestures and marked by cascading jazz roulades in the piano. The second movement, Presto, is a wickedly angular little scherzo; don’t blink – it’s over before you know it. The beautiful slow movement, Lento, concentrates on the strings in the closest thing in this work to a romantic style. Finally, The Allegro non troppo is a tour de force of fusion that one critic has called a “jazz-rock classic.” Perhaps that’s an overstatement, but it is guaranteed that audience and performers will be breathless at the end.

(Program note by Stephen Soderberg for the 2017 Charlottesville Chamber Music Festival)

Nikolai Kapustin Piano Quintet, Op.89

Performed by the Glinka String Quartet

with Pavel Nerses'yan, piano,

Moscow Conservatory, 21 June 2008.

Comments

Post a Comment