Shouts and Echoes

| Les drapeaux. Léon Cogniet (1794-1880)

'You may come this far, and no farther;

here your proud waves must stop.'

Job 38:11 |

1.

In the apartment above the Café Américain, Rick has just refused to sell 'letters of transit' in his possession to the fugitive Czech resistance leader Victor Laszlo so that Laszlo and his wife Ilsa – Rick's former love – can escape Vichy-controlled Casablanca to America. From the cafe downstairs they hear a group of Nazi officers belting out the German patriotic march 'Die Wacht am Rhein' ('Watch on the Rhine'). Rick and Victor emerge and from the stairs look down on the scene in the cafe: the stomping, triumphalist, egomaniacal Nazis – the rest of the clientele dour, defeated, cowering, silently enduring the display. Suddenly, Victor Laszlo makes his move. And right here, in a few measures of music, is where Max Steiner's brilliant juxtaposition turns the movie on a dime, from despair in their present reality to faith in a future reality.

'La Marseillaise' Scene

from the 1942 film Casablanca

The idea for this scene in the 1942 film Casablanca – French patriots drowning out Germans by singing 'La Marseillaise' – undoubtedly came from a scene in the classic 1937 Jean Renoir film Grand Illusion. But Max Steiner's* choice of 'Die Wacht am Rhein' as the song being sung by the Nazi officers reflects the historical French-German enmity and mutual revanchism since at least the 16th century. Claims for the Rhineland were in dispute long before Napoleon.

To fully appreciate Steiner's musical symbolism of crushing the German's 'Watch on the Rhine' with the French 'Marseillaise', it's necessary to recall that the anthem that came to be known as 'La Marseillaise' was originally titled 'Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du Rhin' ('War Song for the [French!] Army of the Rhine'), written in 1792 by Rouget de Lisle as a call to arms to protect the revolutionary French Republic from invasions by a coalition of nation states forming across the Rhine intent on destroying the Revolution.

2.

Arnold Schoenberg arrived in Hollywood in 1933 where he lived the rest of his life. There he knew Jean Renoir and was friends with Max Steiner. It's reasonable to assume he saw both Grand Illusion (released in 1937) and Casablanca (1942) and knew the famous scenes from both films. In 1948 Schoenberg wrote A Survivor from Warsaw.

Accounts of the genesis of this work always point to Russian émigrée choreographer Corinne Chochem as providing its basic story: A group of Jews in the Warsaw ghetto, rounded up by the Nazis for transport to a termination camp, spontaneously begin to sing 'a partisan song' as they are being marched off to die. Schoenberg ended up writing his own version of this basic plot, but he substituted something much more effective than a partisan song. The prisoners, already beaten bloody, are ordered to count off for the impatient Nazi Feldwebel so he knows how many he has for the gas chambers. In the final moments of Survivor from Warsaw, the sprechstimme of the narrator rises to a shout. The prisoners drown out their captors and their inevitable fate:

"They began [to count off] again, first slowly: one, two, three, four, became faster and faster, so fast that it finally sounded like a stampede of wild horses, and all of a sudden, in the middle of it, they began singing [the old prayer they had neglected for so many years - the forgotten creed] the Shema Yisroel [Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God is one ...]"

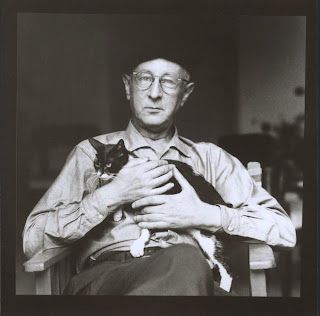

Arnold Schoenberg

A Survivor from Warsaw

Franz Mazura, narr., CBSO Chorus,

City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, cond. Sir Simon Rattle

3.

Whether or not a direct link can be made connecting the Marseillaise scenes in Grand Illusion and Casablanca, and the climax of A Survivor from Warsaw, the case for a deep similarity is compelling.

Music, the wave that memory rides on, is always at the heart of true rebellion. And nothing confounds the tyrant like the song sung in the face of death when the victim is supposed to be pleading surrender and showing obeisance. It's no accident that Mnemosyne, the mother of the Muses, is the Goddess of Memory.

4.

But the memory is fragile, an echo that can easily disappear. The echo dissipates. We forget. We lose the memory, and with it the courage it gave.

David Lewin describes this dissipation near the end of his analysis of Claude Debussy's Feux d'artifice**, a work formed in great part from bits and pieces of the Marseillaise.

'In the fireworks proper we have just witnessed a brilliant display of design, color, transformation, and organized motif. We might imagine ourselves standing somewhere around the Trocadéro or the Eiffel Tower, surrounded by other brilliant symbols of modern French design and civilization. Suddenly we are reminded, by music from somewhere else, far away, out of tune, that the display is meant to celebrate some "old" and "remote" ideas of a republic based upon liberty, equality, and fraternity. We can imagine the sound of the band reaching us from the old, remote Place de la Bastille. But do we notice that reminder? We sense vaguely ... that there are sensible connections between the old music and the display we have just witnessed. But no sooner do we sense that than the old music vanishes and we are suspended, for the last three measures, in the here-and-now of the nocturnal, vaguely "dräuenden" [looming] D♭.' [Underline added.]

Claude Debussy

Feux d'artifice from Preludes (Book II)

Performed by Robert Casadesus

He closes his analysis with an unusually personal comment:

I cannot share the militant nationalism of Debussy's personal thoughts. But I find the rest of the conception [of the work] remarkable, no less so for the ostensible naturalism with which the composition conceals the emotional depth of the idea. Despite the many spasms of American militant nationalism over the past half-century, I am still patriot enough to be bothered that at the climax of our July Fourth celebrations we perform Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture, celebrating not our Declaration of Independence, nor our Constitution, but rather the victory of a Russian Czar over a Napoleonic army.

David Lewin died in 2003. He did not live to see the coronation of the first president to claim the mantle of an American Tsar.

* Recommended reading: Max Steiner: Composing, Casablanca, and the Golden Age of Film Music, by Peter Wegele.

** "Debussy's 'Feux d'artifice'" in David Lewin, Musical Form and Transformation: Four Analytic Essays. (Yale UP, 1993; reprinted Oxford UP, 2007)

Comments

Post a Comment